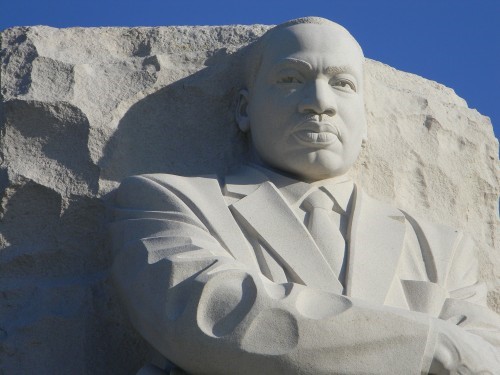

The majestic Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington, DC, reminds America it still has not fully fulfilled its obligations in guaranteeing Black and Brown citizens the promises enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

(Photo by Danny R. Johnson/San Diego County News)

By Danny R. Johnson

WASHINGTON – Four decades after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was gunned down on a motel balcony in Memphis, TN on April 14, 1968, he is still regarded mainly as the Black leader of a movement for Black equality. That assessment, while accurate, is far too restrictive. For all Dr. King did to free Blacks from the yoke of segregation, whites may owe him the greatest debt for liberating them from the burden of America’s centuries-old hypocrisy about race.

In the age of the ascension of President Donald J. Trump and the American and European white nationalists’ movements, Dr. King’s teachings and non-violent tactics are becoming more popular than since the 1960s.

It is only because of Dr. King and the movement that he led that the United States can claim to be the leader of the “free world” without having to be called hypocritical when it comes to racial equality. With the election of Barack Obama, a man of color, as the 44th president in 2008, the world was certain that the United States had ushered in a new age of “post-racial reconciliation”. However, as the world has witnessed since President Obama left office, and the election of Trump – that racial reconciliation talk is going to have to wait, because since day one, Trump has been doing everything in his powers to erase the legacy of Obama.

If it had not been for the courage and vision of Dr. King and the coalition of Black leaders, Black organizations, labor unions, churches, Native American Tribes, Hispanic groups, Jewish theologians, and whites from all walks of life who marched for human rights, vast regions of the United States would have remained morally indistinguishable from South Africa under the old apartheid system, which would have had terrible consequences for America’s standing among nations. How could America have convincingly inveighed against the Iron Curtain while an equally oppressive Jim Crow system remained draped across the South, and most of the country for that matter?

Even after the Supreme Court struck down segregation in 1954, what the world now calls human rights offenses were both law and custom in much of America. Before Dr. King and his movement, a tired and thoroughly respectable Black seamstress like Rosa Parks, and hundreds of Blacks like her, could be thrown into jail and fined simply because she refused to give up her seat on an Alabama bus so a white man could sit down. A six-year-old Black girl like Ruby Bridges could be hectored and spit on by a white New Orleans mob simply because she wanted to go to the same school as white children. A 14-year-old Black boy like Emmett Till could be hunted down and murdered by a Mississippi gang simply because he had supposedly made suggestive remarks to a white woman. Even highly educated Blacks were routinely denied the right to vote or serve on juries. They could not eat at lunch counters, register in motels or use whites-only rest rooms; they could not buy or rent a home wherever they chose. In some rural enclaves in the South, they were even compelled to get off the sidewalk and stand in the street if a white person walked by.

The movement that King led swept all that away. Its victory was so complete that even though those outrages took place within the living memory of the baby boomers, they seem like ancient history. And though this revolution was the product of two centuries of agitation by thousands upon thousands of courageous men and women, Dr. King was its culmination. It is impossible to think of the movement unfolding as it did without him at its helm. He was, as the cliché has it, the right man at the right time.

To begin with, Dr. King was a preacher who spoke in biblical cadences ideally suited to leading a stride toward freedom that found its inspiration in the Old Testament story of the Israelites and the New Testament gospel of Jesus Christ. Being a minister not only put Dr. King in touch with the spirit of the Black masses but also gave him a base within the Black church, then and now the strongest and most independent of Black institutions. However, many veterans of the Civil Rights movement would suggest and argued that the majority of most mega Black churches do not stand for anything but creating wealth for themselves.

Moreover, Dr. King was a man of extraordinary physical courage whose belief in nonviolence never swerved. From the time he assumed leadership of the Montgomery, AL bus boycott in 1955 to his murder 13 years later, he faced hundreds of death threats. His home in Montgomery was bombed, with his wife and young children inside. He was hounded by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, which bugged his telephone and hotel rooms, circulated salacious gossip about him and even tried to force him into committing suicide after he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

As King told the story, the defining moment of his life came during the early days of the bus boycott. A threatening telephone call at midnight alarmed him: “Nigger, we are tired of you and your mess now. And if you aren’t out of this town in three days, we’re going to blow your brains out and blow up your house.” Shaken, King went to the kitchen to pray. “I could hear an inner voice saying to me, ‘Martin Luther, stand up for righteousness. Stand up for justice. Stand up for truth. And lo I will be with you, even until the end of the world.’”

In recent years, however, Dr. King’s most quoted line – “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character” – has been put to uses he would never have endorsed. It has become the slogan for opponents of affirmative action like the Republican Party and Tea Party groups, who insist, incredibly, that had Dr. King lived he would have been marching alongside them. Former hard line Republican Conservative activist, Glenn Beck, held a rally in 2010 in front of the Lincoln Memorial strangely proclaiming that he was “reclaiming the dream” Dr. King spoke about. Beck even chose King’s 47th anniversary of the “I Have a Dream” speech (March on Washington) to announce the creation of his nationwide crusade against “racial preferences.”

Such would-be kidnappers of King’s legacy have chosen a highly selective interpretation of his message. They have filtered out his radicalism and sense of urgency. That most famous speech was studded with demands. “We have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check,” Dr. King admonished. “When the architects of our Republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir,” Dr. King said. “Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check; a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’”

These were not the words of a cardboard saint advocating a greetings card-style version of goodwill. They were the stinging phrases of a prophet, a man demanding justice not just in the hereafter, but also in the here and now.

The time has come for men and women of good will to take up the mantle of non-violence and protest in cities and towns across America to let Democrat and Republican politicians in positions of power know that we the people are here to cast out ballots against them if they do not honor the promissory note as guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution.

Danny R. Johnson is San Diego County News’ Washington, DC based National News Correspondent.