By Danny R. Johnson/San Diego County News National News Editor, and Denise Stapleton, Louisville, KY Freelance Journalist

LOUISVILLE, KY–At 12:40 a.m. March 13, three plainclothes Louisville police officers executed a “no-knock” search warrant, breaking through the door of Breonna Taylor’s apartment where she and her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, were in bed sleeping.

Eight minutes later, Taylor was lying dead in her hallway, shot at least eight times by those same officers, who fired more than 20 shots after Taylor’s boyfriend shot at them, thinking they were intruders, his attorney later said.

Kentucky’s “stand your ground” law allows its residents to use deadly force against intruders they believe is breaking into their home.

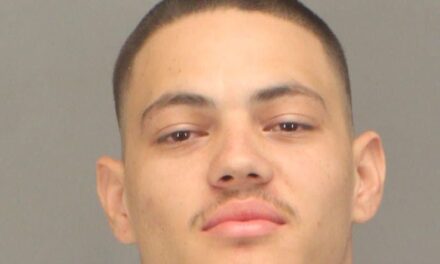

The three Louisville Metro Police officers who fired their guns that night — Sgt. Jonathan Mattingly and officers Brett Hankison and Myles Cosgrove — have been placed on administrative reassignment while the department’s Professional Integrity Unit investigates what happened.

Why is Kenneth Walker charged with attempted murder for allegedly shooting a Louisville police sergeant March 13, who forced his way with two other officers into Breonna Taylor’s apartment while serving a “no-knock” warrant?

When the officers returned fire, Taylor, an ER technician and former Louisville EMT who was unarmed, was struck eight times and died on her hallway.

Commonwealth’s Attorney Tom Wine wouldn’t discuss Walker’s pending prosecution. But Wine told The Courier-Journal in an email that the “stand your ground” statute “is central in any determination of how to proceed.”

Enacted in 2006, the law says it doesn’t apply to force used against police officers — but only if police identify themselves “in accordance with any applicable law.”

Louisville Metro Police have said officers did identify themselves before the early morning raid on Taylor’s home near Iroquois Park, but witnesses have stated otherwise, according to a lawsuit filed April 27 by Taylor’s family against the city.

Peter Kraska, a criminologist at Eastern Kentucky University who has studied no-knock and SWAT team searches, called the March 13 operation at Taylor’s apartment a “classic botched raid.”

Wine, he said, will have to decide whether he wants to antagonize police by dropping the charge or anger “everybody else.”

Metro Council President David James, a Louisville police officer for 20 years, said the two laws stand in deadly conflict, and the city of Louisville should reduce their use to only the most severe investigations that justify their use.

“We have put police and citizens in a very, very bad situation,” he said.

Mayor Greg Fischer said he had asked Chief Steve Conrad to “take another look into this practice.”

But Fraternal Order of Police President Ryan Nichols said in an email that “when used appropriately, no-knock warrants are a valuable tool for law enforcement” and that their use should not be banned or restricted.

Jurors side with defendants in no-knock cases, however, jurors elsewhere have sympathized with defendants who killed police during raids in which they didn’t know law enforcement officers were invading their homes.

In 2016 a jury in Corpus Christi, Texas, for example, acquitted a man who spent 664 days in jail after being charged with attempted capital murder for wounding three officers during a no-knock raid targeted his nephew.

And a grand jury in Burleson County, Texas, refused to indict a man for capital murder after he shot and killed a sheriff’s deputy inside his home during the execution of a no-knock warrant on December 19, 2013.

Kraska and other experts say injuries and deaths, like Taylor’s, are hardly surprising, given that four out of 10 American families are armed. Walker and Taylor thought someone was breaking into their home when Walker fired his weapon, their lawyers have said.

“The use of non-uniformed undercover officers to effect no-knock warrants has become a highly dangerous enterprise for both the policeman and the citizen, who can now fire away without having to try to withdraw,” retired Kentucky Judge Stan Billingsley warned in a 2016 blog post.

Before 1960, it was almost unheard of for officers to force their way unannounced into a home.

But with the proliferation of illegal drugs, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that police may barge into a home if they have a reasonable suspicion that knocking and announcing their presence “under the particular circumstances” would be dangerous or allow suspects to destroy evidence.

That’s what LMPD officers claimed in securing a no-knock warrant for a suspected drug house in the Russell neighborhood and Taylor’s home, which they believed was being used to receive drug shipments.

LMPD spokeswoman Jessie Halladay, citing a pending internal investigation, declined to say who approved the no-knock for Taylor’s apartment.

No-knock searches result in serious, fatal injuries. Across the U.S., the number of no-knock searches has increased from 3,000 in 1981 to 60,000 today, according to Kraska, and the results have included avoidable deaths, gruesome injuries, and multimillion-dollar legal settlements at taxpayer expense.

The New York Times found that between 2010 and 2016, 31 civilians and eight officers died in the execution of no-knock warrants, while the libertarian Cato Institute has reported that 40 bystanders have been killed since the early 1980s.

For example, in Cornelia, Georgia, in 2014, a deputy sheriff secured a no-knock warrant based on false information, breached the door of a home with a battering ram and threw a stun grenade inside during a predawn raid. It landed in a baby’s crib, burning away part of her face. No drugs, no drug dealer, and no weapons were found. The county paid a $3.6 million settlement for the injuries to Bounkham Phonesavanh, known as Baby Bou Bou.

In Atlanta in 2006, after an older woman, Kathryn Johnston, 92, fired one shot into her ceiling, thinking her home was being invaded, police shot and killed her. Their only injuries came from friendly fire. Three officers were sentenced to prison.

In 2013, in Tucson, Arizona, a SWAT team fired 71 shots in seven seconds after making an unannounced entry, killing Jose Guerena, whose family was given a $3.4 million settlement.

According to Kraska, his research shows that in the 15 years ending in 2018, 335 no-knock or “quick knock” raids by SWAT and narcotics teams have resulted in severe or lethal injuries to police or civilians.

No-knock searches often turn up empty. Sixty percent of the time the searches found no illegal drugs or other contraband, as was the case of the police raid on Taylor’s apartment at 3003 Springfield Drive.

The discovery compounded some of the tragedies that raids were conducted at the wrong address or based on false information.

No-knock warrants are allowed in every state except Oregon, where they are prohibited by state law, and in Florida, where they are banned under a state Supreme Court decision.

But Houston’s police department announced last year that it would mostly ban the practice, after a deadly drug raid in which two civilians were killed and four injured. An officer had lied about an undercover informant to justify the warrant, according to press accounts.

Police Chief Art Acevedo announced that officers would need his express permission to search homes without warning from now on.

“I don’t see the value in them,” he stated of no-knock searches. “So, that’s probably going to go by the wayside.”

Louisville Metro Police’s no-knock policy entry requires an officer must have a reasonable suspicion that knocking and announcing his or her presence under the particular circumstances would be dangerous or futile or inhibit the active investigation of the crime through the destruction of evidence. To obtain a “no-knock” search warrant, the officer must obtain prior approval from a lieutenant or above.

In Kentucky’s stand your ground law, a person may use deadly force to protect themselves from someone in the process of unlawfully and forcibly entering their residence or vehicle. The protection does not apply if the person against whom the force is used is a peace officer in the performance of his or her official duties — and the officer identified himself or herself following any applicable law.