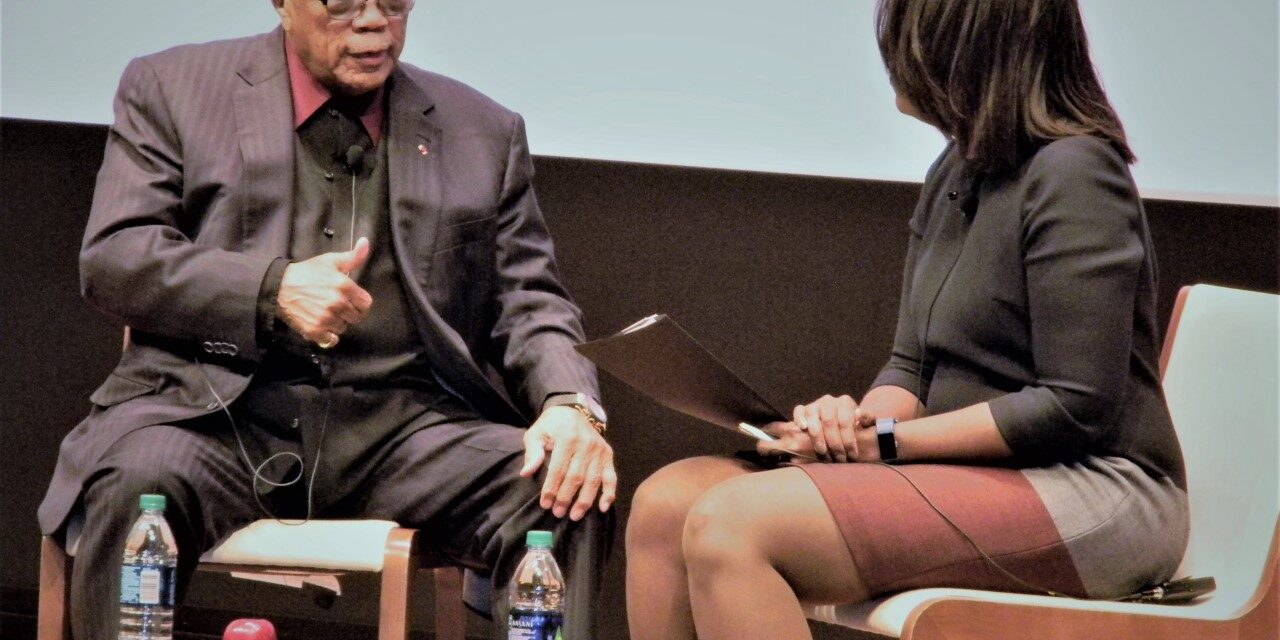

Quincy Jones shared his life story at The National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC on November 30, 2017. (Photo by Danny R. Johnson)

By Danny R. Johnson – Jazz and Pop Music Critic

WASHINGTON, DC – The audience in attendance at the one-hour interview with Quincy Jones at the “On Art and Creativity a Conversation Between Quincy Jones and Dwandalyn Reece,” held November 30th in the Oprah Winfrey Theater, which is housed in Washington, DC’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, left the event with a validation that in its originality, scope, and abundance, Quincy Jones’ music has no rivals in jazz, pop, R&B, Funk, and Latin.

Jones, the 84 year-old recipient of the 2017 Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award, is one of America’s greatest composers whose exceptional talents and accomplishments can easily be ignored entirely in discussions of American music, which is an indication of a separatism that continues to vex the nation’s cultural habits. The question of how he measures up to his contemporaries in the American composers tradition is one I’ll leave to music academics historians to judge.

Like Mozart, Quincy Jones wrote and continuous to write music specifically designed for dance, concert and, again like Mozart, fudged the distinction between the two by the originality and consistency of his vision. Still, if Jones’ music stands apart, it is entirely rooted in what we recognize as the “Quincy Technique,” a music principle usually, but by no means always, exhibits some or all of the standard characteristics: an equation of composition and improvisation, robust rhythms, dance band instrumentation, blues and song frameworks, and blues tonality.

Jones was asked by interviewer Dwandalyn Reece what were some of the musical attributes he looks for when producing music for singers and instrumentalists: “I regarded my entire orchestra as one large instrument, and I try to play on that instrument to the fullest of its capabilities,” Jones explained. He went on to share his approach in creating that “magic” with the instrumentalist. “My goal was always and always has been to mold the music around the singer or performer – finding a good fit for every instrumentalist is the challenge,” he concluded.

In the same period, Jones told Reece, “You can’t write music effectively unless you know how the person who will perform it is comfortable making the piece his or her own.”

Quincy Jones’ long career as a music composer lends insight into popular music’s influence on the television and film media. In 1951, a teenaged Jones began working as a trumpet player and arranger for Lionel Hampton. During his early career, he played with some of the best known names in Black bebop and jazz, performers such as Count Basie, Clark Terry, Ray Charles, Billy Eckstine, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sarah Vaughan. His musical talent allowed him to tour Europe, the Middle East and South Africa during the 1950s. In 1957, he studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. During this period he also became a major publisher of music.

However, failed business ventures in 1959 forced him to sell his music publishing catalogue. Jones overcame this major financial setback by working as an executive at A and M Records and by working as an arranger for Dinah Washington in New York City. Signed as an executive in 1961 and then rising to the position of Vice President of Mercury Records in 1964, Jones was the first African American executive at a major record label.

In 1961, Jet magazine, a weekly entertainment periodical directed to an African American readership, awarded him the title of best arranger and composer. But despite honors from his African American community and excellent critical reviews, Jones recognized that jazz music was not earning high record sales. He decided then to produce more commercial songs. In 1963, he branched out to develop the talent of a white teenage singer, Lesley Gore, with whom he recorded the pop hit “It’s My Party.” Jones continued to work with talented white artists such as Frank Sinatra for whom he conducted and arranged Sinatra: Live in Las Vegas at the Sands with Count Basie (1966).

But television news reports were increasingly presenting images of discord and America was coming to terms with growing racial conflict. Amidst the struggle for civil rights, Jones worked in Hollywood to help destroy the negative stereotypes of African Americans. In 1965, he was hired to score the film Mirage, starring Gregory Peck and he scored In The Heat Of The Night (1967) starring the top box office star of the era, Sydney Poitier.

January 30, 2004: Quincy Jones with music legend Ray Charles, as he receives the Grammy President’s Merit Award at Ray Charles Enterprises in Los Angeles. In their hometown of Seattle, at the age of 14, Quincy Jones became lifelong friends with the 16-year-old Ray Charles. (Photo by NARAS)

In 1965, Jones reinforced his ability to compose music for the screen by scoring the pilot and eight episodes of the dramatic television series Ironside. In creating the Ironside theme, he was the first composer to utilize a synthesizer in the arrangement of a television score. During the same year he composed the theme to the television movie, Split Second to an Epitaph. Jones also wrote the theme song for Bill Cosby’s first situation comedy, The Bill Cosby Show (NBC, 1970) and went on to score 56 episodes.

In a brief two week period between film and television scores, Jones returned to record making with the jazz album, Walking. The album won a Grammy as best jazz performance by a large group in 1969.

In 1972, Jones wrote the theme to the NBC Mystery Movie series and his momentum in the television industry continued to grow. During the same year, he scored 26 episodes of The Bill Cosby Variety Series and in 1973, he composed the theme to the comedy program, Sanford and Son, starring comedian Redd Foxx.

In 1974, soon after his Body Heat album reached the top of the music charts, Jones suffered from health problems. A brain aneurysm required two surgical procedures and a promise to stop playing the trumpet.

After a four year hiatus, during which he concentrated on his own music productions, Jones returned to television in 1977 to score the ABC miniseries, Roots, one of the highest rated programs in television history. His score accented the exploration of African chants and rhythms as indigenous to American culture and garnered Jones an Emmy Award. Coinciding with this success in television, he scored The Wiz (1977), a Universal Pictures all Black version of The Wizard of Oz, starring Diana Ross and Michael Jackson.

From the time between 1963, when Jones entered the Hollywood film industry as a film composer, and 1990 he had earned thirty-eight film credits. Most notably, he co-produced the critically acclaimed film, The Color Purple (1985) with director Steven Spielberg. In 1994, Jones was honored with an Academy Award for his achievements in the film industry.

1984: Michael Jackson won a record eight Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year and Record of the Year for Thriller — the bestselling album of all time — with record producer Quincy Jones during the Grammy Awards in Los Angeles. (Photo by NARAS)

Despite his success in television and film, Quincy Jones never lost interest in spotting talent in black music. During the 1970s, he continued to cultivate new performers in this arena. He created technically advanced, funk influenced albums for The Brothers Johnson, Chaka Kahn and Rufus. In 1977, he produced Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall album, which succeeded in selling seven million albums–before the invention of MTV. His record breaking pop album Thriller, for Michael Jackson in 1984, became a musical landmark.

In 1981, Jones left A&M and formed his own Qwest label at Warner Brothers. The Qwest label produced hits for Patty Austin and James Ingram and captured Lena Horne’s performance on Broadway; these recording projects earned him Grammy awards. In 1985, Jones produced the all-star recording of “We Are The World” to help performer Harry Belafonte realize a charity drive to raise world awareness of famine. From the song’s popular music video, Quincy Jones, long been familiar through his music, became a recognizable face to the general public. He raised money for Jesse Jackson’s historic run for the Democratic Presidential nomination in 1988 and produced The Jesse Jackson Show in 1990, granting a forum to a high profile black figure in U.S. politics.

Jones also discovered a larger television audience by producing situation comedies. In 1991, Fresh Prince of Bel-Air premiered starring a popular rap artist, Will Smith, to become a highly rated program on NBC. In 1990, Jones formed the multi-media entertainment organization, Quincy Jones Entertainment Company and Quincy Jones Broadcasting, to acquire television and radio properties. In 1995, Jones repeated his television success with the situation comedy, In the House, starring Debbie Allen and rap artist LL Cool J.

While overcoming racial barriers and redefining several genres in music composition, Quincy Jones’ creative persistence in the music business helped to maneuver black music across the color line of the musical mainstream and into every form of media expression. Jones’ body of work spans six decades and opened the door for the growth of successful black entrepreneurs in television, film and music. Since Miles Davis’ death, many critics cited Quincy Jones as the only remaining figure from the bebop era who has stayed contemporary and whose work continues to have an impact on these three closely integrated media industries.