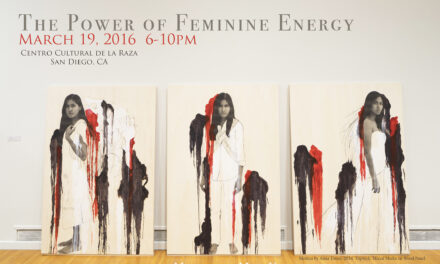

(L-R) The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra (JLCO) Music Director Victor Goines, swinging it with guest clarinet players Anat Cohen, Janelle Reichman, and Ken Peplowski. (Photo by Frank Stewart)

By Danny R. Johnson – Jazz and Pop Music Critic

NEW YORK, NY – When band leader, composer, clarinet player, and swing music powerhouse Benny Goodman died in his sleep on the afternoon of June 13, 1986, at 77, the emotions conjured by his name are unique to those few who transcended the specific talents and who came to represent an era. The Jazz At Lincoln Orchestra (JLCO), along with Wynton Marsalis, music director Victor Goines, clarinetists Anat Cohen, Janelle Reichman, Ken Peplowski, JLCO member Ted Nash, vibraphonist Joseph Doubleday, and vocalist Veronica Swift, reminded us on January 13, 2018, at The Rose Theater in New York, why Goodman’s obsessionist swing music is still immensely popular 31 years after his death.

The JLCO is to be commended for headlining a dynamic and bravura line-up of talented artists, who faithfully and professionally gave the sold-out concert a memorable reflection of the music made famous by Goodman.

It should be noted that Goodman always had good soloists in his band, among them were Harry James, and Ziggy Elman, a trumpeter in the James mold, Lionel Hampton and saxophonist George Auld. And sometimes he had superb ones, including Cootie Williams, Bunny Berigan, Charlie Christian, Teddy Wilson, and Goodman himself, all of whom were among the best jazz players of their era.

Clarinetist Anat Cohen accompanied by the JLCO performed a passionate rendition of Benny Goodman’s “China Boy.” (Photo by Frank Stewart)

The JLCO dedicated the evening to Goodman’s January 16, 1938 memorable Carnegie Hall debut, which featured Count Basie and Duke Ellington. Music Director Victor Goines stated that Goodman “was one of the most outstanding clarinetists in the history of jazz…for him to play this concert at Carnegie Hall was a major event.” Goines went on to state that Goodman took a risk by headlining a cast of African American and white artists all together on the same stage in a major venue was unprecedented.

Which is why Goines, who is one of the most prodigiously talented and successful musicians in jazz orchestration, directed the Goodman music for the evening with a keen sense of speech, or conversation, that lies in the work of so many of the best music directors. What stood out in the JLCO concert is the speech like quality achieved basically by Goines’ management of the artists’ musical selections and individual notes or, in the case of quick passages, short phrases.

Goines continuously was changing inflection. As in the case of Cohen performing China Boy, Nash, Peplowski, and Reichman’s (performing I Got Rhythm) solos and interaction with the band, were all consistent in attacking some notes sharply; lets others slide into existence. The JLCO and guest artists would swell some notes and diminish others; and at other times in musical selections Don’t Be That Way, Sing, Sing, Sing, and Avalon, the musicians would often let the pitch of a long, held note sag briefly, or let it drop off at the end, which was an effective Goodman technique he often executed.

Goodman was one of the most passionate players in jazz during his reign as the “Pied Piper of Swing.“ At times, when he felt the commercial necessities upon him, he could play with a deep simplicity, but when he was playing what he wanted, he was endlessly hot! All of the guest clarinet performers, but especially Cohen and Goines, were most animated in coloring their notes with growls and hot rasps.

Janelle Reichman performed a riveting rendition of Benny Goodman’s “I Got Rhythm,” which was accompanied by a dazzling vibes performance with Joseph Doubleday and the JLCO. (Photo by Frank Stewart)

Goines’ arrangement and rendition of One O’Clock Jump had Cohen consummately using both the blue third and blue seventh at a time when the blue notes as well as lines – or, in some cases, instead of lines. This sort of thing is exceedingly difficult to analyze because it is subtle and depends on fractional changes in volume, pitch and timbre.

Goines brilliantly managed to duplicate the pulsing riffs that have been the driving force in Goodman’s big band ever since he formed it in the 1930s, was alive and well in vibraphonist Joseph Doubleday’s performance with the JLCO on the musical selection Avalon. Doubleday’s dazzling vibes work was a core of a performance that ranged from the familiar, openly swinging attack that enlivened the JLCO and relived the Benny Goodman Quartet, which often featured Hampton on vibes of the 1940s to a light, airy soft‐shoe effect, accompanied only by Goines on clarinet that became a provocatively extended introduction to Avalon.

Yet, in truth, the JLCO and guest artists’ entire manner of playing was filled with the sound of New Orleans, a city whose music heavily influenced the Benny Goodman sound. Goines, a native of New Orleans, arranged the music with this expressed point in mind.

The essential element of Goodman’s music came from the old tradition rooted in New Orleans. Goines and the JLCO, including all the solo players, had all the ingredients of the perfect Benny Goodman New Orleans style musical gumbo recipe – the intonation was excellent. The tone was warm and full and completely in control. The lower registers were rich, and the dexterity was quick enough to allow the clarinet soloists to play faster than most musicians on the jazz circuit today.