During his seven-decade career, one of the most prolific and revered producers in music history, Jones touched on Jazz, Soul, Funk, Disco, Rock, Pop, and Hip-Hop.

By Danny R. Johnson – Jazz and Pop Music Critic

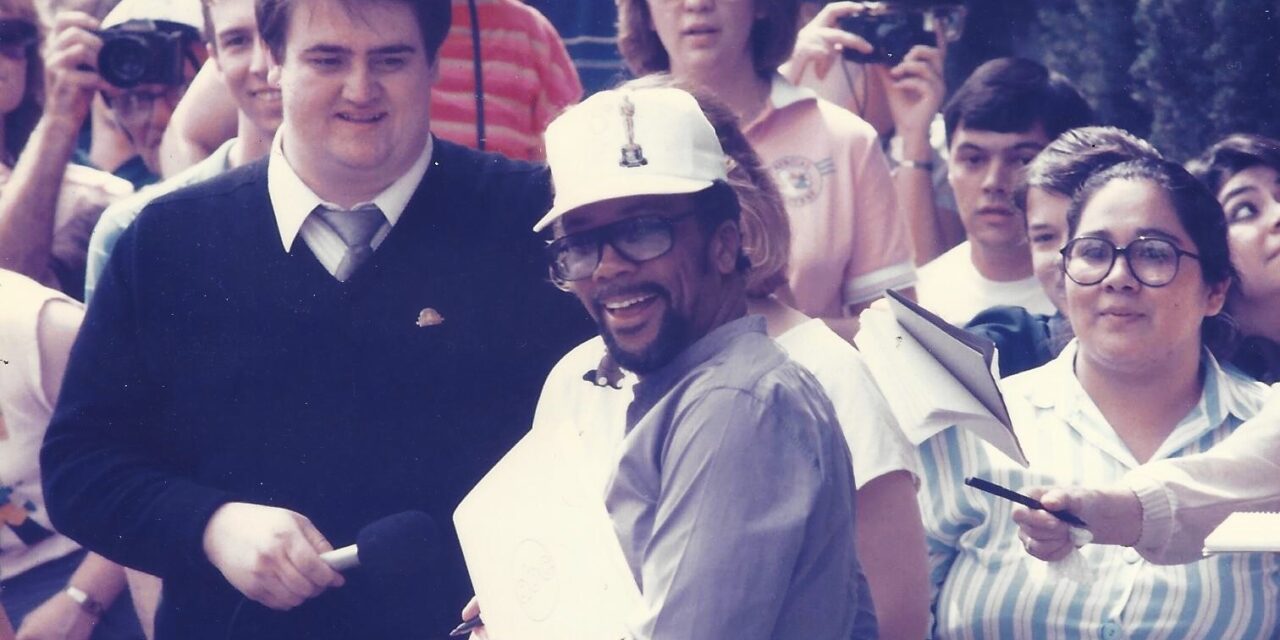

LOS ANGELES – Upon hearing of the death of Quincy Jones on November 3, I reflected on the last time I talked with him. The audience in attendance at the one-hour interview with Quincy Jones at the “On Art and Creativity: A Conversation Between Quincy Jones and Dwandalyn Reece,” held November 30, 2017, in the Oprah Winfrey Theater, which is housed in Washington, DC National Museum of African American History and Culture, left the event with a validation that in its originality, scope, and abundance, Quincy Jones’ music had no rivals in Jazz, Pop, R&B, Funk, and Latin.

Jones was then eighty-four and was a recent recipient of the 2017 Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award, is one of America’s greatest composers whose exceptional talents and accomplishments can easily be ignored entirely in discussions of American music, which is an indication of a separatism that continues to vex the nation’s cultural habits. The question of how he measures up to his contemporaries in the American composer’s tradition is one I will leave to music academic historians to judge.

Like Mozart, Quincy Jones wrote and continued to write music specifically designed for dance concerts and, again, fudged the distinction between the two by the originality and consistency of his vision. Still, if Jones’ music stands apart, it is entirely rooted in what we recognize as the “Quincy Technique,” a music principle usually, but by no means always, exhibits some or all of the standard characteristics: an equation of composition and improvisation, robust rhythms, dance band instrumentation, blues and song frameworks, and blues tonality.

Jones was asked by interviewer Dwandalyn Reece what were some of the musical attributes he looks for when producing music for singers and instrumentalists: “I regarded my entire orchestra as one large instrument, and I try to play on that instrument to the fullest of its capabilities,” Jones explained. He shared his approach to creating that “magic” with the instrumentalist. “My goal was always and always has been to mold the music around the singer or performer – finding a good fit for every instrumentalist is the challenge,” he concluded.

In the same period, Jones told Reece, “You can’t write music effectively unless you know how the person who will perform it is comfortable making the piece his or her own.”

Quincy Jones’ lengthy career as a music composer lends insight into popular music’s influence on the television and film media. In 1951, a teenager named Jones began working as a trumpet player and arranger for Lionel Hampton. During his early career, he played with some of the best-known names in Black Bebop and jazz, performers such as Count Basie, Clark Terry, Ray Charles, Billy Eckstine, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sarah Vaughan. His musical talent allowed him to tour Europe, the Middle East, and South Africa during the 1950s. In 1957, he studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. During this period, he also became a significant publisher of music.

However, failed business ventures in 1959 forced him to sell his music publishing catalog. Jones overcame this major financial setback by working as an executive at A&M Records and as an arranger for Dinah Washington in New York City. Signed as an executive in 1961 and then rising to Vice President of Mercury Records in 1964, Jones was the first African American executive at a major record label.

In 1961, Jet magazine, a weekly entertainment periodical directed to an African American readership, awarded him the title of best arranger and composer. However, despite honors from his African American community and excellent critical reviews, Jones recognized that jazz music was not earning high record sales. He decided then to produce more commercial songs. In 1963, he branched out to develop the talent of a teenage white singer, Lesley Gore, with whom he recorded the pop hit “It’s My Party.” Jones continued to collaborate with talented white artists such as Frank Sinatra, for whom he conducted and arranged Sinatra: Live in Las Vegas at the Sands with Count Basie (1966).

But television news reports were increasingly presenting images of discord, and America was coming to terms with growing racial conflict. Amidst the struggle for civil rights, Jones worked in Hollywood to help destroy the negative stereotypes of African Americans. In 1965, he was hired to score the film Mirage, starring Gregory Peck, and he scored In the Heat of The Night (1967), starring the top box office star of the era, Sydney Poitier.

In 1965, Jones reinforced his ability to compose music for the screen by scoring the pilot and eight episodes of the dramatic television series Ironside. In creating the Ironside theme, he was the first composer to utilize a synthesizer to arrange a television score. During the same year, he composed the theme for the television movie Split Second to an Epitaph. Jones also wrote the theme song for Bill Cosby’s first situation comedy, The Bill Cosby Show (NBC, 1970), and went on to score fifty-six episodes.

Jones returned to record-making between film and television scores in two weeks with the jazz album Walking. The album won a Grammy for Best Jazz Performance by a large group in 1969.

In 1972, Jones wrote the theme for the NBC Mystery Movie series, and his momentum in the television industry continued to grow. During the same year, he scored twenty-six episodes of The Bill Cosby Variety Series, and in 1973, he composed the theme for the comedy program Sanford and Son, starring comedian Redd Foxx.

In 1974, after his Body Heat album reached the top of the music charts, Jones suffered from health problems. A brain aneurysm required two surgical procedures and a promise to stop playing the trumpet.

After a four-year hiatus, during which he concentrated on his music productions, Jones returned to television in 1977 to score the ABC miniseries Roots, one of television’s highest-rated programs. His score accented the exploration of African chants and rhythms as indigenous to American culture and garnered Jones an Emmy Award. Coinciding with this success in television, he scored The Wiz (1977), a Universal Pictures all-Black version of The Wizard of Oz, starring Diana Ross and Michael Jackson.

From 1963, when Jones entered the Hollywood film industry as a film composer, and in 1990, he earned thirty-eight film credits. He co-produced the critically acclaimed film The Color Purple (1985) with director Steven Spielberg. In 1994, Jones was honored with an Academy Award for his achievements in the film industry.

Quincy Jones never lost interest in spotting Black music despite his success in television and film. During the 1970s, he continued to cultivate new performers in this arena. He created technically advanced, funk-influenced albums for The Brothers Johnson, Chaka Kahn, and Rufus. In 1977, he produced Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall album, which succeeded in selling seven million albums–before the invention of MTV. His record-breaking pop album Thriller for Michael Jackson in 1984 became a musical landmark.

In 1981 Jones left A&M and formed his own Qwest label at Warner Brothers. The Qwest label produced hits for Patty Austin and James Ingram and captured Lena Horne’s performance on Broadway; these recording projects earned him Grammy awards. In 1985, Jones made the all-star recording of “We Are the World” to help performer Harry Belafonte realize a charity drive to raise world awareness of famine. From the song’s popular music video, Quincy Jones, long been familiar through his music, became a recognizable face to the public. He raised money for Jesse Jackson’s historic run for the Democratic Presidential nomination in 1988. He produced The Jesse Jackson Show in 1990, granting a forum to a high-profile black figure in U.S. politics.

Jones also discovered a larger television audience by producing situation comedies. 1991 Fresh Prince of Bel-Air premiered, starring a famous rap artist, Will Smith, to become a highly-rated program on NBC. In 1990, Jones formed the multi-media entertainment organization Quincy Jones Entertainment Company and Quincy Jones Broadcasting to acquire television and radio properties. 1995, Jones repeated his television success with the situation comedy In the House, starring Debbie Allen and rap artist LL Cool J.

Quincy Jones’ music stands apart and could be equal to that of the great Duke Ellington. Jones’s music in its entirety is rooted in what we recognize as jazz principles and usually, but not consistently, exhibits some or all of the standard characteristics, which he carried over to Pop, R&B, and Blues: an equation of composition and improvisation, robust rhythms, dance band instrumentation, blues and song framework, and blues tonality.

While overcoming racial barriers and redefining several genres in music composition, Quincy Jones’ creative persistence in the music business helped to maneuver Black music across the color line of the musical mainstream and into every form of media expression. Jones’ work spans six decades and opened the door for the growth of successful Black entrepreneurs in television, film, and music. Since Miles Davis’ death, many critics have cited Quincy Jones as the only remaining figure from the Bebop era who stayed contemporary and whose work had a tremendous impact on these three tightly integrated media industries.