By Danny R. Johnson – Political News Editor

WASHINGTON, DC–More than 60 years after its delivery, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous refrain of “I Have a Dream” remains a cry for freedom adopted by activists worldwide, from Tiananmen Square to the West Bank. But to fully appreciate the magnitude of King’s 1963 speech at the March on Washington, we must first understand the context of its delivery. King spoke of an America whose Black population was “sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.” That he framed his words with images of slavery was no accident.

President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, but the Jim Crow laws, which mandated racial segregation, were still in full force throughout the South. Just ten weeks before King’s speech, Governor George Wallace had attempted to obstruct two African American students from enrolling at the University of Alabama; President John F. Kennedy had to send the National Guard to make the governor stand down. Meanwhile, the civil rights movement was blossoming across the country. Peaceful sit-ins and boycotts—à la Rosa Parks—had yielded to violent action by 1963, most notably in the Birmingham riot of May; as King noted in his speech, these “whirlwinds of revolt,” characterized by riots and militant demonstrations, blustered through 100 towns and cities nationwide.

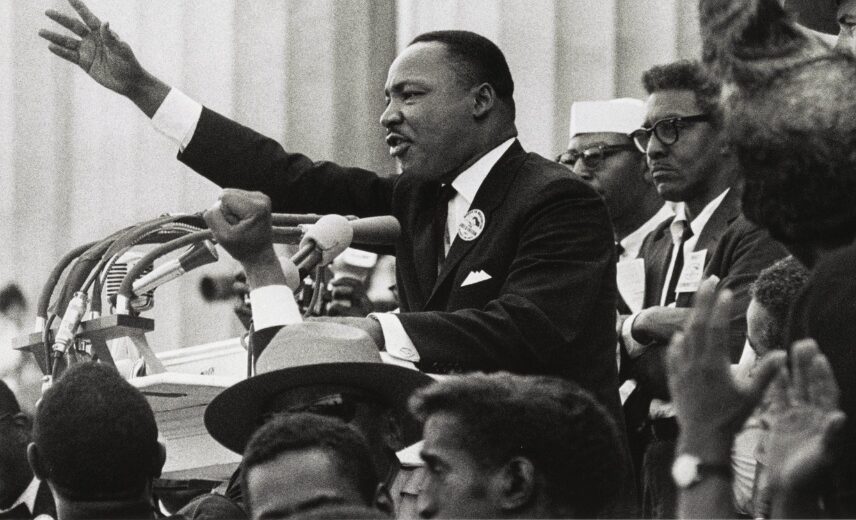

The environment was ripe for change. To this end, King helped organize, with the assistance of labor unions, human rights advocates, Jewish leaders, and hundreds of other religious groups, an ambitious political rally in the nation’s capital on August 28, 1963, whereby roughly 250,000 protesters gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial. By late afternoon, the marchers had begun to fade in the oppressive summer heat. The author Norman Mailer recalled “a little of the muted disappointment which attacks the crowd in the seventh inning of a crucial baseball game when the score has gone eleven-to-three.” Many were already leaving by the time King was slated to speak.

King experienced a tumultuous journey in the months leading up to August 28, 1963. He had been the victim of multiple death threats and attempts on his life and attracted fierce opposition from within the civil rights movement. Malcolm X, a leader of the Nation of Islam, had disparagingly dubbed the march the “Farce on Washington.” King had also been arrested, for the 13th time, during the Birmingham campaign only a few months earlier. Nevertheless, he now found himself at the wheel of a massive vehicle for change; almost a quarter of a million activists anxiously waited for him to begin his address. As he strode to the podium, the words of a song his friend Mahalia Jackson, a gospel singer, had sung earlier that day reverberated in his ears: “I’ve been’ buked, and I’ve been scorned … I cannot make it alone.” She had performed this old spiritual at King’s request, and his mood may have mirrored the song’s words.

“Tell them about the dream, Martin! ” Mahalia Jackson cried. At this point, King’s oration leaped to life. It was in this melancholy vein that King began his speech. He first adhered closely to his prepared text, grandly recapitulating the many injustices faced by African Americans. His background as a Southern Baptist preacher was readily apparent; he spoke slowly and paused regularly, imbuing each word with ministerial gravity.

King began by invoking Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address, setting his words in the appropriate temporal context: “Five score years ago …” This was the first in several instances when King deliberately anchored his speech in the architectural documents of Western literature and then appropriated the original ideas to suit his ends. King also made explicit reference to the U.S. Constitution. By associating his speech with the nation’s founding documents, King infused his words with credibility and familiarity.

Similarly, King effectively employed the extended metaphor of unpaid debt to justify the African-American rationale for protest. First, he likened the “unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” guaranteed by the Declaration of Independence to a “promissory note” for all Americans. Then he characterized the March on Washington as a mission “to cash this check” that was 100 years overdue. He lamented how, over the previous century, America’s “bank of justice” had marked this check with “insufficient funds” for its “citizens of color,” and he explained the refusal of African Americans to accept this injustice. This metaphor served as a narration of the events leading up to the march and emphasized that “the Negro’s legitimate discontent” was directed at the legislature. Indeed, King made the point that the underlying aim of the protest—”citizenship rights” for all people—was no different from that of the nation’s Founding Fathers in 1776.

King also introduced several biblical allusions. Like Lincoln, King had a deep knowledge of scripture—he quoted verses from Amos and Isaiah and subtly referenced passages from Psalms and Galatians. These allusions resonated with large portions of his audience and added depth to his words. We can also draw similarities between King’s depiction of “the Negro” who “finds himself an exile in his land” and the plight of the Israelites in the Book of Exodus. This comparison painted the civil rights movement in a sympathetic light and inspired hope. Under the leadership of the prophet Moses, the Israelites finally escaped oppression and found deliverance in the promised land; King implied that African Americans could find solace in this historical precedent and that they, too, would be liberated in due course.

King’s speech had certainly been eloquent up to this point, but many audience members had expected something more, given his stellar reputation as an orator. John Lewis, a student leader of the march who later became a congressman, recalled that the speech thus far “was not nearly as powerful as many I had heard him make.” Mahalia Jackson must have shared his sentiment, for as King neared the end of his prepared remarks, she suddenly cried out: “Tell them about the dream, Martin! Tell them about the dream!”

At this point, King’s oration leaped to life. The speech was spontaneous and grew from an articulate summary of grievances into something transcendent. Jackson had heard him speak about his dream earlier that year; King now seized this established motif and ran with it. He sharply contrasted racism, tolerance, and prejudice with liberality: “I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former enslavers will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” King also drew upon his situation to stimulate emotion, invoking his children to symbolize innocence and virtue: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” The parallel construction of these sentences reaffirmed the shift in King’s speech from a bleak account of past wrongs to a sincere expression of hope for the future.

Remarkably, King’s discourse was largely spontaneous. He had experimented with the refrain of “I have a dream” before but had not included it in his prepared text. In retrospect, it is significant that King used the word dream to convey his vision. We tend to label dreams as unreal conditions, but King’s doctorate in theology suggests that he may have intended to frame his dream in the biblical sense. Particularly in the Old Testament, dreams conveyed God’s plan and signified a promise that would inevitably be fulfilled. Knowing this, it is possible to interpret his dream as a promise to the American people that one day, freedom would “ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city” across the country.

King’s words are as accurate today as they were in Washington 60 years ago.

The speech has played an integral role in improving race relations since the 1960s, but King’s dream has yet to be fully realized—he recognized that the events of 1963 were “not an end, but a beginning.” Congress passed the Civil Rights Act a year after his speech, but recently, controversy over what King in his “Dream” speech called “the winds of police brutality,” such as in the cases of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, has “staggered” the country. At the same time, Black-on-Black crime in the inner cities is not being addressed. The Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, but debate continues to rage over new voter identification laws that reduce turnout among African Americans. Protesters marched in 1963 under the collective banner of “Jobs and Freedom,” yet wages and income for African Americans, Indigenous people, and Latinos remain low and out of reach.

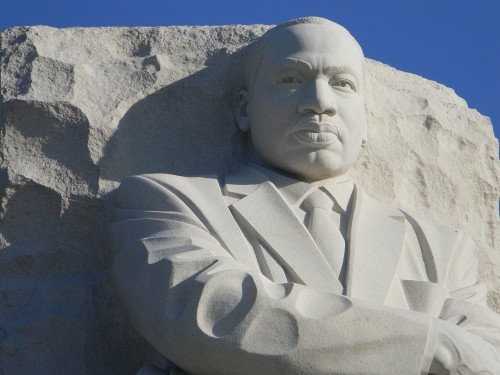

As President Jimmy Carter noted, King, through his campaign for equal rights, not only helped free African Americans but “helped to free all people.”

As we honor the 60th Anniversary of the March on Washington, the inescapable truth is that racism and hate are alive and well in America and are a way of life for millions of Americans. The old scourge of racism, spoken or unspoken, acknowledged, or unacknowledged, subtle, or sometimes not so subtle, the disease of racism permeates and poisons every institution of American society. Today, King’s message resonates with the fierce urgency of now and the hard work we all must muster to eliminate the disease of racism permanently and unrelentingly.

It is unlikely King ever envisaged that on the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington, the day’s celebrations would culminate with America’s elected and reelected first Black president, Barack Obama (2009-2017), and a current Black female Vice President, Kamala Harris, still, in 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. dared to dream. Today, the “beautiful symphony of brotherhood” that King anticipated for his four children is a far brighter prospect than when he delivered his speech. Today, we harbor hope that tomorrow, all of God’s children will finally be able to hold hands and repeat after King: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”