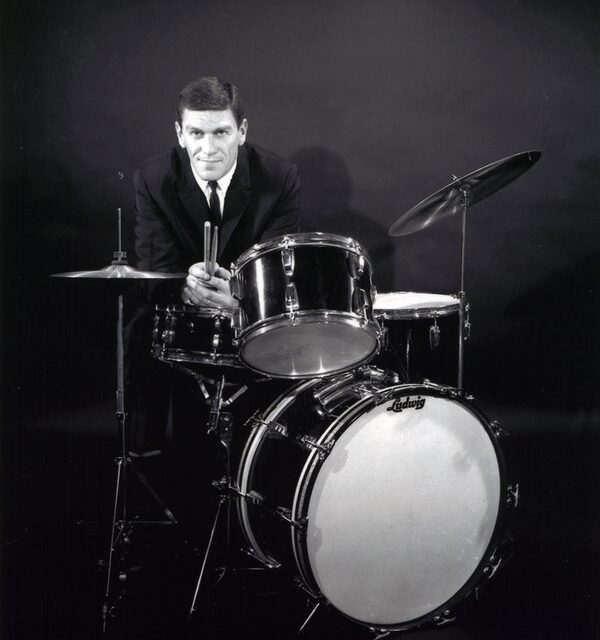

Stan Levey: Jazz Heavyweight

Frank R. Hayde

224 pages

ISBN: #13-978-1-59580-086-2

Santa Monica Press

2016

By Danny R. Johnson

Jazz and Pop Music Critic

Between 1945 and 1950, two gods dominated American music – Bird and Diz. Every young jazz musician and composer, regardless of instrument, emulated them. Pop arrangers and film composers and conservatory students entertained themselves by appropriating the hip chords, cool dissonances, and in wit of bop.

If you ask any of the freshman contemporary students of jazz at Julliard or Berkeley – “Have you ever heard of a drummer by the name of Stan Levey?” The answer you would probably get from the majority of them is – “Stan who?”

Stan Levey is one of the most benign and omnipresent figures in jazz history, and one of the least recognized. Despite a career in which he made formidable contributions to nearly every jazz generation from the late 1940s to the mid1970s, the adjective “underrated” clings to his name like ivy on a wall. Yet he was by no means underappreciated by those who knew his work.

Stan Levey was the original drummer and member of the Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker band that ushered in that new sound of 1945 called “Bebop.”

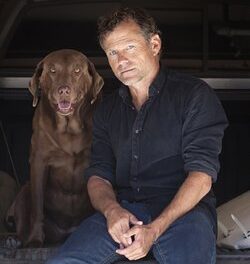

Writer and author, Frank R. Hayde’s new book, “Stan Levey – Jazz Heavyweight, The Authorized Biography,” explores Levey’s complicated life filled with musical triumphs, personal observations and personal setbacks. The author utilized Levey’s personal perspectives he recorded and wrote over the years prior to his death on August 19, 2005, and included Levey’s excerpts from the interviews along with his narrative, which significantly added a personal connection readers will have with Levey when reading the book.

First let’s put some things in perspective before delving into the meat of the book. Jazz drummer Stan Levey was an exceptional artist. Many of the jazz titans – Diz, Bird, Max Roach, Benny Goodman, Miles Davis, Woody Herman, Stan Kenton, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and Peggy Lee, (just to name a few), were all indebted fans who insisted that he be their drummer. Critics came to admire his imperturbable dignity as much as his manifold talent (though historians tend to overlook Levey’s contributions to big band music). He made few records as a leader and none of them sold very well. When the accomplishments of his peers were recounted, Levey’s were often forgotten.

Well, Stan gets the last word and there are no interruptions or cynics to refute the record. Hayde allows Levey’s writings and recordings to speak for themselves as a frank, no nonsense witness to the interesting musical personalities he interacted with – all devoid of any over-romanticizing or self-pity, which was one of the hallmark characteristics of Stan Levey.

A Clock and Chick Webb Inspires Drummer Boy

Adolph Stan Levey was born April 5, 1926 in Philadelphia to Esther (Essie) and Dave Levey, Lithuanian Jews who were struggling European immigrants with their only child. Stan’s mother was a chronic alcoholic and his father was a boxing manager and part owner of a used car lot. They were always at each other’s throats arguing. Stan is recorded in the book as stating, “It didn’t take much to affect her [Essie]. A drink or two and pow! She was slurring her words and staggering.”

Being the only child and constantly having to listen to his parents fuss and argue, Stan would sit in his room with no toys with only a bed, a closet, a little bureau and a clock. The only sound was his clock with its loud and percussive sound, which Stan said he “could hear it all the way from the bathroom.”

Dave and Stan were not bonded and did not get along very well. As a fight manager in the 1930s and 1940s Philly, Dave occupied a low level position in the national crime syndicate which dominated the prize fighting industry on all levels. Which meant that he did not see his father very often because he was always working. Essie was a domestic housekeeper and quite intelligent considering all the things she had to put up with. It was Essie who had musical talent and who Stan most looked to for affection and support, which Essie was able to provide though somewhat sporadically.

But there was something about that old clock which provided comfort and respite from his parent’s arguing. “I’d take a couple of pencils and improvise beats between the clock’s ticking: One-two-three, one-two-three, FOUR!” Stan stated.

Stan would become so obsess with this rhythm he would tap his spoon and fork on a glass of milk or dinner plate which would drive Dave crazy! Essie would use his outburst as an opportunity to admonish Dave to buy Stan a drum set. When he was 10, Essie relentlessly nagged Dave until he finally took Stan to see legendary bandleader and drummer, Chick Webb, an event which inspired this big Jewish kid from Philly to aspire to be a drummer.

While a teenager, Stan stood at six-foot-two and was considered a heavyweight in the 1940s. He spent a lot of time in the gym having sparring rounds with Dave’s boxers. Stan weighed 178 pounds “but he had hands like a catcher’s mitt and a heavy jaw anchored by a brick of a chin,” Hayde stated in the book.

Dave saw potential in his son becoming a boxer, not a musician. So, he takes him to the gym with him and introduces him to all the guys. Stan is of course elated that his father is paying attention to him and taking him to see fights. But as he was to find out later it was all for show and profit and nothing else. The only consolation was Dave finally buying him a kid’s drum set for Christmas! Later Dave and Essie eventually divorced and Stan lived with his mother.

Stan taught himself how to play the drums because his family did not have money for a teacher. Even though he was right-handed, Stan was playing left-handed, but he made a conscious decision not to change his style because it worked well for him. Hayde stated that Stan’s “southpaw stance was a distinguishing quirk and a source of curiosity for young drummers who studied him.”

When Dave moved out Stan felt a sense of abandonment and even more loneliness than ever before. He drops out of school just as he was beginning the ninth grade. Stan tries to connect with his father through the ring and helping to sell cars, but nothing seems to connect.

Bebop Jazz Drummer Stan Levey was the first white drummer who could really play modern music, and he was forceful, energetic, and an excellent player.

Stan Hooks Up With Dizzy

At 16, and after several dismal failures as a fighter and non-interest in used cars, Stan was at a cross road and needed some sense of direction from somebody pretty fast. Stan credits luck, a knack to really want to be a drummer, and a considerable amount of chutzpa helped him to connect with Dizzy.

Here is how he tells the story of how they met: “I’m walking down Eleventh Street in Philly and I hear this trumpet coming through the window, and I say, Man, it sounds like Roy Eldridge. And I go up these steps to this bar…and I am listening.”

Stan stated that Dizzy came up to him and Stan immediately told him that he plays drum. “Well, come on up and sit in,” Dizzy replied. This invitation will open more doors for Stan than he could ever imagine.

After sitting in on several sessions with the band and loving every minute of it, Dizzy invites Stan to serve as the substitute drummer for the band. After a few practice sessions, Stan gets the hang of it and is working for Diz for $18 a week!

All of these seemingly positive events boosted Stan’s confidence and gave him a new sense of purpose in life. When you get hooked up with somebody like Diz – doors will start to open up as Stan soon found out. One day, while Diz and the cats were playing at a local Philly club, Benny Goodman’s manager came in and said he was looking for a drummer to replace the one who just left and Benny’s band member, Zoot Sims, remembered Stan and advised management to check him out.

With Dizzy’s blessings and encouragement, Stan goes to meet with Benny at the local theater where they were performing, goes to the backstage dressing room and Stan writes what he witness: “He has his back to me. I walk in, and …he’s urinating in the sink!” Stan was so excited that he going to play for “The Benny Goodman” – he goes home and tells his mother and she doesn’t believe him and tell him to “shut up and go to sleep.”

Benny was a gifted musician but had some strange ways according to Stan. He kept Stan throughout his one week gig in Philly but never once looked at him nor did he announce Stan’s name as the drummer. Benny called everybody ‘Pops’ and couldn’t remember the names of his own family.

Stan had a profound admiration for Dizzy because not only was he a good teacher, he was a positive role model and father figure. Stan recounted that Dizzy was very intellectual, committed family man, did not drink, and a shrewd businessman.

When Dizzy broke the news to Stan that the band was moving to New York, he was devastated. The only man he really looked up to was about to leave. It wasn’t soon after Dizzy left that Stan became acquainted with a trumpet plyer named Nick Travis. And Nick will be the one who first introduce Stan to drugs. Stan and Nick began to pop ‘bennies” and smoke pot and life was about to get more interesting.

Stan Team Up with an Erratic Bird in Flight

After an unfortunate incident with the Philly police department, Stan decided it’s time to head north to New York. When he arrives at age 17 to 52nd Street, the world’s epicenter for jazz activity in the 1940s, he is reunited with Diz and encounters Bird. Diz was the kind of guy once he takes you under his wings – you are family – unless you mess up. When Diz hired and recommended Stan to other black bandleaders in New York City on the basis of virtue of his abilities rather than he was Jewish or white, he held his ground and took no slack. Diz would often tell his critics –“Hey, when you can play better than him, not as good, but better, you’ll have the job.”

The book notes that Gillespie and Miles stood their ground in the face of harsh remarks by some black musicians for employing white sidemen such as Stan.

Stan totally immerse himself into the New York City jazz scene and interacted and lived with a number of musicians such as, Max Roach, Charlie Parker, and Miles Davis. “It was like the gym in Philly,” he says about one particularly melodious apartment building filled with jazz musicians, “with me the only white face.”

The author, Frank Hayde writes about Levey’s playing at various venues in New York, and particularly the “Jazz At The Philharmonic” tours in which jazz promoter Norman Granz made it a point to make a statement against Jim Crow by presenting interracial groups of musicians, insisted on integrated accommodations, and sometimes lost money by refusing to play for segregated audiences.

When Stan first met Bird, he was only 17 when he hooked him up on heroin. Bird was like that says Stan. He could be an intellect who read everything and was always up-to-date on the latest news, but when it’s time for that fix, he changed into another person on the dark side. Stan described his relationship with Bird like this: “The reason Bird turns people on is to get them involved. Once you’re in the club…then we all got out and hustle money. When he’s low, he got a friend to go to. When a pusher gets tough, or some junkie gets dangerous, he’s got me to protect him.”

Eventually, Stan’s drug dependency landed him in prison. In the early 1950s, after serving a nineteen-month prison sentence for selling heroin, Levey vowed that his life had to change. He got out of prison with a determination to never again touch the stuff and break from his idol Charlie Parker. And he was successful in doing so – the man never touched drugs from that day to the day he died. Though he briefly played some engagements with Parker, Stan knew that being around his idol was another ticket to prison and he was having none of it. Stan’s wife Angela was the bulwark between Bird and Stan – she got on Bird’s nerves on many of occasions whenever there were any hints that he was trying to set her husband up.

After Stan, Dizzy, singer June Christy and Bird did a European tour with the Stan Kenton Orchestra in 1954, and returned to the states, Stan took a photo of a bewildered and falling apart Bird for the last time on the tarmac of the airport. Little did he know that the great Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker would be dead in just one year at the age of 34.

West Coast Jazz Scene and Civility

West Coast jazz refers to many styles of jazz music that developed around Los Angeles and San Francisco during the 1950s. West Coast jazz is often seen as a subgenre of cool jazz, which featured a less feverish, calmer style than bebop or hard bop. The music tended to be more heavily organized, and more often composition-based. While this style was prominent for a while, it was by no means the only style of jazz played on the West Coast, which exhibited more variety than could be conveyed by a simple name.

Cool jazz reflected the laid back atmosphere of the West Coast jazz sound with celebrated musicians like Dave Brubeck dominating the genre. But Stan, Bird and Diz brought bebop to California a few years earlier, and became instrumental in the development of West Coast jazz.

Equally at home in big bands and small groups, Stan Levey was right in the midst of it. East Coast Jazz or West Coast ‘Cool Jazz’, Stan was in the midst. Stan worked with George Auld, Freddie Slack, Stan Kenton, and Charlie Ventura, and in 1945 subbed for Dave Tough in Woody Herman’s band. Following a few years of partial inactivity, he returned to Stan Kenton band in 1952.

“It was tough and physically demanding job,” Stan told Ken Burns of PBS. “I almost had to start working out weights to keep up with it – probably the band was too overpowering. You could not move or maneuver the thing too easily.” Happier in the small group environment, Stan later joined Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-stars in California, where he remained for six years. After touring with vocalists Peggy Lee and Ella Fitzgerald, he became part of the prestigious L.A. studio scene and recorded with everyone from Henry Mancini to Frank Sinatra.

Stan Levey’s story is an American success story which has been told millions of time before. The son and grandson of European Jewish immigrants who came to America in search of a better life for themselves and their children. His story seems to cry out for novelistic scope and nuance. Stan’s musical accomplishments were diverse: he was the first great drummer of the bebop era, the anchor of many fiercely competitive and innovative bands and orchestras, a pacesetter for trios, quintets, and quartets, and a nurturer of talent whose unselfish generosity was rewarded by hundreds of those he met over his lifetime.

With all these accomplishments, you would think a person like Stan Levey would be satisfied – and all of his accomplishments were satisfying. But the greatest achievement of this gifted artist is his three sons he admitted: “My three sons are my proudest achievements. Chris and David are both top radiologists, and Robert is a master painter. I’m very lucky. See, Angela was like an old Sicilian wife. That was her life, those boys.”

Well done Stan Levey and your legacy lives on!