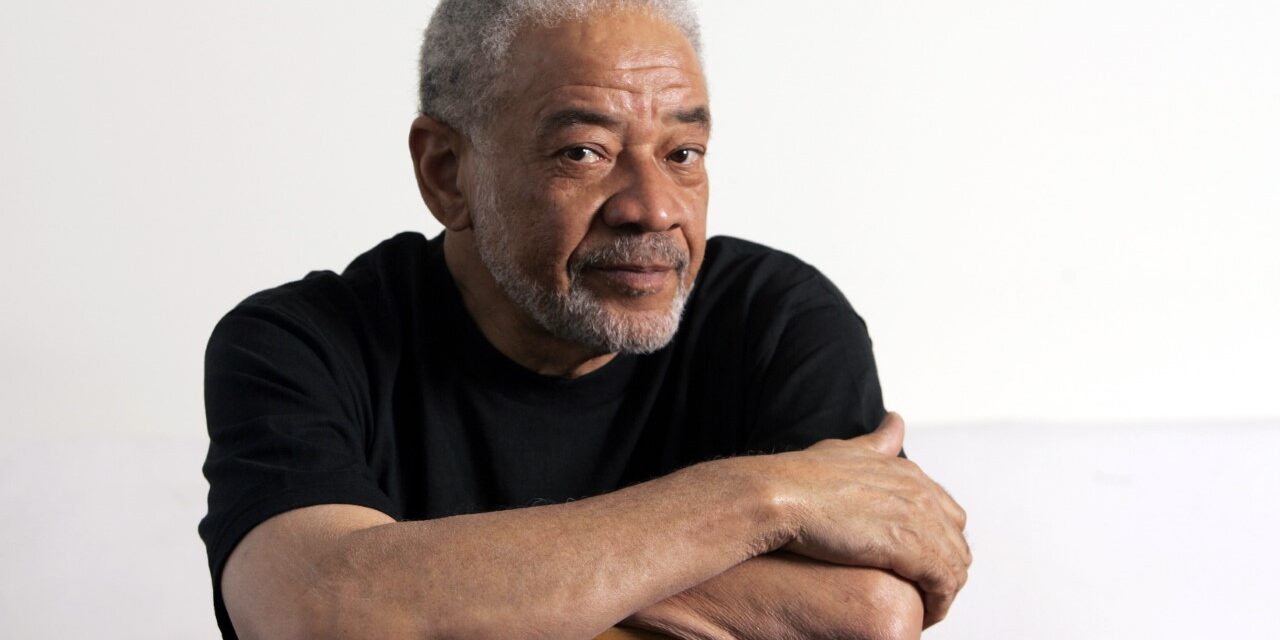

By Danny R. Johnson/Jazz and Pop Music Critic

Grammy-winning songwriter and singer of ‘Lean on Me’ was one of the 20th century’s most recognized pop and soul artist

LOS ANGELES – For several decades, perplexed interviewers had been asking Bill Withers, the great, reclusive soul singer, variations of the same questions: Did he miss the musical life he’d once had and did he ever imagine returning to it? In 1985, having already built an impressive legacy—Gold plaques, Hot 100 hits, Grammy wins—he left the industry and never looked back. The answer was always firm, unsentimental, and unambiguous: No. We aren’t used to seeing those who step out of the spotlight never yearn for it, but Withers found freedom in retirement.

For him, there was nothing to do but enjoy a quiet life, unbothered. The thrall of celebrity didn’t have any hold on him. “I’m not motivated to wanna draw attention to myself or travel all over the place,” he said in 2010. “There was a time for that. When it was done it was done. Now it’s something else.” Withers, one of the most impactful soul musicians of the 20th century, died earlier this week from heart complications. He was 81. The singer-songwriter was a withdrawn genius who let his body of work speak for itself and quit on his own terms. His songs are etched into the American imagination forever. He is a character rarely seen in popular music: a shy guy turned mastercraftsman who left a massive cultural footprint writing and singing simple songs, and then decided to forsake fame in favor of a simple life. The music that Withers made was reflective of his rearing. As he once put it, “Everyone is pretty much a synopsis of where they come from.” Fittingly, his songs were secular spirituals born of a small-town community nearly cutoff in the Jim Crow South, and they spoke to the souls of the ordinary blue-collar folks in black communities and beyond. “He’s the last African-American Everyman,” Questlove told Rolling Stone in 2015. “Bill Withers is the closest thing black people have to a Bruce Springsteen.”

Bill Withers was born in Slab Fork, West Virginia in 1938. A coal miner’s son and the youngest of six children, Withers had no interest in music as a kid. He stuttered and was awkward. His grandfather had been born into slavery, he lived on the border of a segregated town, and threats of racism loomed large. His father died when he was 13, and he wanted nothing more than to escape this small, poor, dead-end place. “Growing up I was mostly interested in getting away from where I grew up,” he said in the 2005 doc, As I Am. At 17, he enlisted in the Navy, where he served for nine years.

It’s clear the simplicity of his rural upbringing, the regimented nature of his military service, and his segregated existence colored the way he made music and the way he saw the music industry. He had a knack for getting to the heart of a feeling, which made his deeply personal songs feel innate to the human experience. His music was unadorned but carefully crafted. And he would come to resent white men lording over him. His career and his departure were the culmination of his less-is-more worldview.

After getting a hold of his speech impediment and quitting his Navy job as an aircraft mechanic, he re-entered the workforce in 1965 doing jobs he was overqualified for at $3 an hour. His interest in performing was prompted by a night at an Oakland club; an exasperated manager remarked that he was paying Lou Rawls too much money—$2000 a week—for the singer to be late. Withers realized he was in the wrong business. He bought a guitar at a pawn shop, taught himself to play, and fiddled with it between shifts at his job working at an aircraft parts factory. He learned enough to write songs.

Withers eventually saved enough to cut a demo, and his songwriting impressed black industry executive Clarence Avant, founder of indie label Sussex. Avant brought on Stax keyboardist Booker T. Jones to produce Withers’ debut, and with a band of talented players in tow, they laid down Just As I Am in only a few days. Even after his deal and the release of his first songs, he didn’t quit his day job, an early sign of his dream-proof practicality. He was laid off at the factory just before the album’s release in 1971. He got two letters shortly thereafter: “One was asking me to come back to my job. The other was inviting me on to Johnny Carson.” He chose Carson, and on that episode, he performed “Ain’t No Sunshine,” one of the best songs ever written. It lived on the charts for a while, but it lives on everywhere else.

At 32, having already lived a full life, Withers was now in a second act as an intrepid soul man. A slew of unforgettable hits followed: the sympathetic anthem “Lean on Me,” the uninhibited “Use Me,” the strolling romp “Lovely Day,” and the couple’s retreat “Just the Two of Us.” The sheer range was as impressive as the songs themselves. In a relatively short period of time, he managed to run the emotional gamut. Each of his most treasured tracks is like a little world all to itself, drawing out a single, ordinary moment into an immeasurable number of microscopic details. Everything else blurs.

There was a powerful accessibility to his best songs, the ones that have become part of the cultural fabric of America; they weren’t just clean-cut, simple expressions of emotion, they had no-frills arrangements, too—in part because he was an “untrained” musician but more so because he purposefully sought something more fundamental. He often downplayed his skills as a musician, but he had a way with writing and arranging music that felt elaborate, involved, and impenetrable. His playing was expressive.

Beyond the colossal impact and little revelations of his most well-known songs, there is gorgeous portraiture across his catalog. There’s a tactileness to “Grandma’s Hands,” soothing an unwed mother, picking the young Bill up each time he fell, warm to the touch and embracing. On “Make a Smile for Me,” you can feel the infectious, awe-inspiring, mood-altering power of the simplest gesture. “Hello Like Before” has in it the reanimating glow of lost love made new again by a chance encounter, the nostalgia-induced bliss of old feelings welling up to the surface.

He released seven albums in eight years in the 1970s—among them, his commercial apex, 1972’s Still Bill, his break-up album, 1974’s Justments, and his groovy comeback, 1977’s Menagerie. He released an epilogue of sorts in 1985, and then he abandoned the music industry for good. He had been in a cold war with CBS A&R man Mickey Ikeman, who was flat-out avoiding him and dodging his calls for about three years, and he’d had enough. “I just felt confined that this one guy that really had nothing to do with any black music at all could just shut me down like that. It bothered me. So, I’ve never signed with another record company since,” he told NPR in 2007.

Withers clearly resented the idea that the soul music he created was governed by a force that didn’t truly understand it. His departure from the industry had something to do with the many white gatekeepers policing black art. “You gonna tell me the history of the blues? I am the goddamn blues. Look at me,” he said in the As I Am doc. “Shit, I’m from West Virginia, I’m the first man in my family not to work in the coal mines, my mother scrubbed floors on her knees for a living, and you’re going to tell me about the goddamn blues because you read some book written by John Hammond? Kiss my ass.” He referred to such figures as “blaxperts,” white execs who insisted they knew more about black music than he did. He dissented. He would not produce his secular spirituals under such circumstances—which was to say, he wouldn’t make music at all.

“If you truly look at anyone in black entertainment who has declared a next level thinking of genius there has been some complications along the way,” Questlove postulates in the documentary, Devil’s Pie: D’Angelo. “Either in early exits, jail, religion, and some just stall, or use time, chronic lateness or just not showing up at all as a way to control things. These are just some of the symptoms. Anyone who is black that started in meager or so-so conditions that are not of the privileged of the world—when they finally transform to a higher level, it is guilt they feel. And that is one thing that every black genius wrestles with.” Artists like D’Angelo and Lauryn Hill have used time to forgo the pressures of their genius. But for Withers, not showing up at all was a form of control, and he never seemed to feel any guilt in doing so. After all, his expectations were always modest.

Withers broke free from the constraints of his genius to live a normal life. In this way, his career is a triumph over the debilitating fog of celebrity. He left an indelible mark on music, and on American culture, and then rode off into the sunset.

Despite his decision to cut his career short, his truncated discography, and the many “what ifs?” about what could have been, Bill Withers still reached rarefied air—not just for a stuttering boy from Slab Fork, but for any great musician of the modern era. In 2005, he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. Ten years after that, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, somewhat to his surprise—and by the virtuoso Stevie Wonder, no less—but anyone who has really listened to his songs knows they are a part of the bedrock of the soul music canon.

Withers was a singular purveyor of the relationship between physical and intangible sensations; the vacuums that distance and space create; how the image of having a shoulder to cry on begets the comfort of