By Danny R. Johnson – Washington, DC Correspondent

NBA legend Bill Russell’s daughter’s account of the racism he endured is being shared on social media after his death.

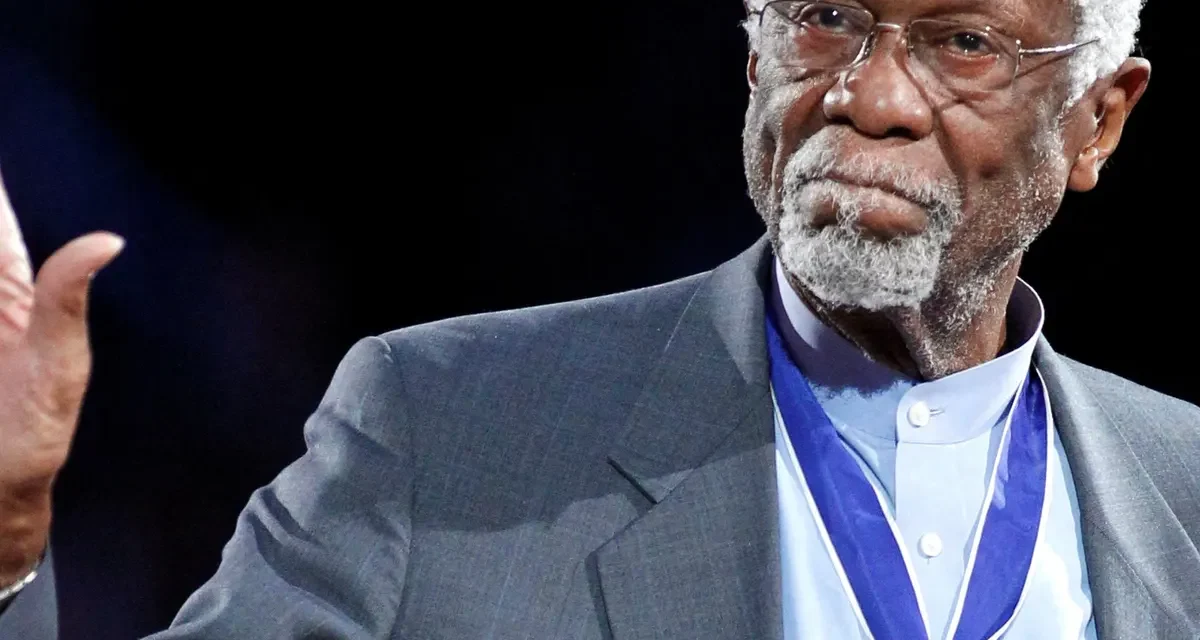

Russell died on Sunday at the age of 88 with his wife Jeannine by his side, his family said in a statement on Twitter. The most prolific winner in NBA history, Russell was the centerpiece of the Boston Celtics dynasty that won 11 championships in 13 years. His last two NBA titles were as the first Black coach in any major U.S. sport. A Hall of Famer, five-time Most Valuable Player, and 12-time All-Star, Russell also won two college titles and an Olympic gold medal.

When Russell was elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1975, Red Auerbach, who orchestrated his arrival as a Celtic and coached him on nine championship teams, called him “the single most devastating force in history of the game.”

He was not alone in that view: In a 1980 poll of basketball writers (long before Michael Jordan and LeBron James entered the scene), Russell was voted nothing less than the greatest player in the history of the NBA.

Former Senator Bill Bradley, who faced Russell with the Knicks in the 1960s, viewed him as “the smartest player ever to play the game and the epitome of a team leader.”

Russell was remembered as well for his visibility on civil rights issues.

He took part in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and was seated in the front row of the crowd to hear the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech. He went to Mississippi after the civil rights activist Medgar Evers was murdered and worked with Evers’s brother, Charles, to open an integrated basketball camp in Jackson. He was among a group of prominent Black athletes who supported Muhammad Ali when Ali refused induction into the armed forces during the Vietnam War.

“But for all the winning, Bill’s understanding of the struggle is what illuminated his life,” his family said.

“From boycotting a 1961 exhibition game to unmask too-long-tolerated discrimination, to leading Mississippi’s first integrated basketball camp in the combustible wake of Medgar Evans’ assassination, to decades of activism ultimately recognized by his receipt of the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2010, Bill called out injustice with an unforgiving candor that he intended would disrupt the status quo, and with a powerful example that, though never his humble intention, will forever inspire teamwork selflessness and thoughtful change.”

Since news of Russell’s death, a tweet sharing an extract from a column Russell’s daughter Karen Russell wrote for The New York Times in 1987 about the racism her father faced while playing for the Boston Celtics.

“When he first went to Boston in 1956, the Celtics’ only black player, fans and sportswriters subjected him to the worst kind of unbridled bigotry,” she wrote in the article.

She also recalled how her family had once come home from a weekend away to find out they had been robbed.

“Our house was in shambles, and ”N***A” was spray-painted on the walls. The burglars had poured beer on the pool table and ripped up the felt. They had broken into my father’s trophy case and smashed most of the trophies,” she wrote.

“I was petrified and shocked at the mess; everyone was distraught. The police came, and after a while, they left. My parents then pulled back their bedcovers to discover that the burglars had defecated in their bed.”

She said that vandals would tip over her family’s garbage cans every time the Celtics went on the road.

“My father went to the police station to complain. The police told him that raccoons were responsible, so he asked where he could apply for a gun permit,” she wrote. “The raccoons never came back.”

But she said that the “only time we were terrified” was after her father wrote about racism in professional basketball for The Saturday Evening Post.

“He earned the nickname Felton X,” she wrote. “We received threatening letters, and my parents notified the Federal Bureau of Investigation.” And she noted that when her father got his FBI file years later, he discovered it was littered with references to him as ”an arrogant Negro who won’t sign autographs for white children.” Former president Barack Obama was among those who have paid tribute to Russell.

“Today, we lost a giant. As tall as Bill Russell stood, his legacy rises far higher—both as a player and as a person,” Obama wrote.

“Perhaps more than anyone else, Bill knew what it took to win and what it took to lead. On the court, he was the greatest champion in basketball history. Off of it, he was a civil rights trailblazer—marching with Dr. King and standing with Muhammad Ali. Bill endured insults and vandalism for decades but never let it stop him from speaking up for what’s right.”

Russell’s family called on others to follow his example.

“We hope each of us can find a new way to act or speak up with Bill’s uncompromising, dignified, and always constructive commitment to principle,” the family said. “That would be one last and lasting win for our beloved #6.”